The family of Robert and Anne Codrington are depicted as a group of mourners on the base of the memorial to Robert in Bristol Cathedral. There are supposed to be 17 children but is this the correct number?

The family of Robert and Anne Codrington are depicted as a group of mourners on the base of the memorial to Robert in Bristol Cathedral. There are supposed to be 17 children but is this the correct number?

Robert Codrington, 9x great-grandfather, died on 17th February 1618/19 in the precinct of Bristol Cathedral at the age of just 46. [i]

Robert Codrington, 9x great-grandfather, died on 17th February 1618/19 in the precinct of Bristol Cathedral at the age of just 46. [i]

“… being somewhat crased in Bodie, but in moste perfect sence and mynde.”

His will leaves money to his children but does not specifically mention the names of his younger sons, only his daughters and the eldest son John.

Anne, his widow, remarried in 1626 [to a man 20 years her junior], and there are a number of court cases regarding inheritance at about this time.

… Anne married and took to husband one Ralph Marshe, gentleman, whom she brought in marriage very great advancement, howbeit he, thirstinge after his owne profitt, neglected the children of Anne, and sought to abridge them of their portions and Annuities bequeathed to them …

These cases have provided some additional information that has helped to identify the children – in particular the sons – of Robert and Anne Codrington.

With the details of the court cases, the transcription of the will and all the additional detail in the memorial you would think that it would be easy to identify all the family members correctly but it appears that this is not the case and it just makes things even more confusing.

[i] The funeral of Robert and the memorial and tomb in Bristol Cathedral cost £32 in 1619 which would be about £4400 today – pretty good value for money.

Robert

Robert was born about 1573, the eldest son of Simon Codrington of Codrington, Wapley and Didmarton.

He attended Winchester College and then Magdalen College at Oxford, matriculating on 9 Feb 1587/88 at the age of 14.

After leaving Oxford in 1591 he was admitted to Grey’s Inn to train as a lawyer.

The Oxford record, from which these dates are taken, also says that he is “perhaps father of the next named [Robert] and of John 1605″ showing that this record is by no means certain, especially as the date for John is also incorrect.

Provision was made in 1593 [i] for his marriage to Anne Stubbes and they married in Shrivenham, Berkshire [now Oxfordshire] two years later.

The family lived in Bristol, in a house close to the Cathedral – that was probably destroyed in the riots of 1831 – and this is also where Robert died: a house was remembered in the area with stained glass bearing the Codrington arms in the windows. [2]

[i] RHC shows this date as 1583 – 10 years earlier – in order to fit in with the birth of John, Robert’s eldest son that was incorrectly calculated from the Oxford University records as 1590 instead of 1600.

This meant that he also never found the correct marriage record for Robert and Anne in 1595.

He had identified the correct birth of John [confirmed by the will of his grand-father] in his earlier work [3] but then changed his mind in [2] presumably based only on the Oxford record.

Mourners

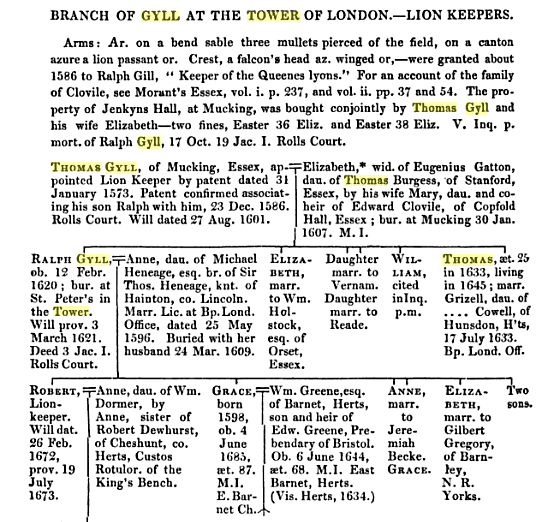

On his elaborate memorial in Bristol Cathedral [at the east end of the north aisle of the choir], below the two main figures of Robert and Anne, there is a frieze of mourners.

On his elaborate memorial in Bristol Cathedral [at the east end of the north aisle of the choir], below the two main figures of Robert and Anne, there is a frieze of mourners.

There are 7 kneeling male figures on the left and 7 female figures on the right.

One of these female figures is described as “a curious effigy of two figures representing twins” [1] which makes 8 daughters alive when Robert died.

There are also two prone figures representing children who died in infancy – the names of these two are not known.

The Latin inscription below the memorial [i] – mentions 9 daughters and 8 sons, assuming that all the figures in the frieze are children, but this cannot be fully reconciled with evidence from the will of Robert or any of the subsequent court records.

One way to make the number add up is to forget about the frieze being a group of mourners and view it just as a family group – the two central figures being Robert and Anne themselves.

The two main figures on the frieze are dressed in a similar manner to the larger ones of Robert and Anne above – the male figure in particular – and all the other sons are dressed in cloaks.

The two main figures on the frieze are dressed in a similar manner to the larger ones of Robert and Anne above – the male figure in particular – and all the other sons are dressed in cloaks.

The male also appears to have a full beard and John the eldest son would only have been 18 at this time, so if this is Robert then it must also be Anne which makes the number of daughters and sons identified in other sources, as correct.

If the main female figure is Anne then the next two are twin daughters Elizabeth and Anne which also fits in with the will where they are “elder daughters”, otherwise this leaves one daughter unnamed in the will.

Restoration

A plaque above the memorial shows that the memorial was moved and restored by the Bethel Codrington family in 1840, which included the repainting of the crests.

HOC MONUMENTUM AVITUM REFICIEND. ET RESTAURAND.

PIE CURAVIT BETHEL CODRINGTON BARONETUS MDCCCXL

“This memorial bird damages. And restored. [With loving care] Bethel Codrington Baronet.”

I was not able to translate PIE CURAVIT – Google says “sweet cured” which is clearly not correct!

PIA CURAVIT translates as “loving care” which I have assumed is closer to the truth.

The Latin inscription below the tomb may be original and mention the 9 daughters (only 7 are mentioned in the will) and 8 sons of which only 6 are known by name.

As the tomb was erected after the death of Robert it should have reflected all the children who were alive at the time, however this may not be the case.

To the most noble Lord Robert Codrington, of Codrington in the county of Gloucester, renowned by the representations of his friends, and highly respected for his fidelity and uprightness of conduct. He was free’d from life’s prison February 14th 1618 aged 46. His excellent wife lady Anna Codrington begat him 8 sons and 9 daughters. In consequence of her tender affection and respect for him, she erected this tomb and monument.

One way to interpret this is that ALL the children of Robert and Anne are shown and not just those that were alive when Robert died.

The two prone figures could be those that died at birth rather than as infants and several of the others may have died before Robert.

If there are 9 girls then at least one of them had died in addition to the prone figure – as there were no mention of twins in the will it would seem reasonable to assume that it was one of the twins that died.

Or possibly it was the eldest (first-born) and the twins are Elizabeth and Anne, as these two are named together at one point.

Frieze

The will of Robert identifies his eldest son as John, born 1600, but he also mentions his six younger sons.

This makes 7 sons, all of who were alive when Robert died in 1618.

[See also I, Robert]

In the will Robert mentions his daughters Elizabeth and Anne before the six younger boys.

“The two elder daughters are to have £20 a year each until marriage and all are to be brought up by their mother. The six younger sons are to have £10 apiece yearly for meat, drink and apparel, with good education.” [2]

If we accept that the main female figure is Anne then this makes the next figure – the twins – as these two daughters but if the main figure is the oldest daughter, Elizabeth, then that makes Anne one of the twins – and the other must be dead, as no twins are mentioned in the will.

Robert and Anne were married in 1595 and eldest son John born in 1600 which leaves 5 years in which other children could have been born, so some of the daughters are older than John, the eldest son.

The term “younger” could just mean younger than the two oldest girls. John is later instructed to give £20 to the “said younger sons” within a year of the death of Robert, and it is not clear if this included John himself.

This interpretation gives a total of 14 children – 7 boys and 7 girls – and two who died in infancy, making 16 with one son unaccounted for.

If we assume the central “mourners” as Anne and eldest son John this would allow room for the missing son, Robert, but I think they are more likely to be Robert and Anne – in which case there are only six sons, including John.

To contradict this the main female character is not dressed the same as Anne, above, and is dressed the same as all the other girls – it is only the main male figure that is throwing this into confusion by being practically identical to Robert, including the armour he is wearing, unless this is simply representing John as being the heir [clone] of Robert.

Twins

The right-hand side of the frieze is actually a bit scary – the girls heads slowly turn around as you go from oldest to youngest, but at least they are not spinning around.

The right-hand side of the frieze is actually a bit scary – the girls heads slowly turn around as you go from oldest to youngest, but at least they are not spinning around.

I cannot see any other interpretation of the second image other than as twins, and because they are shown together I am assuming that they were both alive in 1619.

But there is no mention of twins in the will, in fact all seven daughters are listed individually in order.

There could be several reasons for this, including that one of the twins had already died, which is probably the most likely explanation.

If this were the case then it would make the main female figure as eldest daughter, Elizabeth, and consequently the main male figure would not be Robert but eldest son John – and six other sons, which provides its own complications.

Weepers

Weepers are common on elaborate tombs of this period, but the rules about who is a weeper seem to be different for each memorial.

They are most commonly the children of the deceased but there could also be other relatives or even friends, particularly those of high standing.

What may be confusing in this case is that Anne is shown as one of the main figures but was not actually dead so she could also, technically, be shown as a weeper.

In this example from the tomb of Richard Stone, 1607 [St Mary’s, Holme-next-the-Sea in Norfolk] the boys are clearly show dressed in a similar fashion to each other, but the eldest son does not look anything like his father.

In this example from the tomb of Richard Stone, 1607 [St Mary’s, Holme-next-the-Sea in Norfolk] the boys are clearly show dressed in a similar fashion to each other, but the eldest son does not look anything like his father.

However in a description of another monument in Bristol cathedral, Sir Henry Newton of Barrs Court, 1599 …

On the left side are the two sons, the elder dressed in armour of the same type as the father’s, every detail being copied.

The description of the Codrington memorial from “Effigies of Bristol” seems to follow a similar design with the eldest son John dressed identically to his father.

Under the figures is a long, narrow panel containing small kneeling ” weepers,” viz. seventeen children; in the centre is a desk with open books, and on the right [left] are eight male figures, all kneeling except the youngest, which is lying down. The first is dressed in armour similar to the man, and the remaining ones wear long cloaks over doublet and trunk hose.

On the left [right] are Nine female figures, all kneeling except the youngest, which is lying down. Amongst them is a curious effigy of two figures representing twins. All are dressed similarly to the woman, except they have no head-dresses, the hair being elaborately braided and rolled high off the forehead.

There are several references to memorial weepers in “Effigies” and in all cases the figures are interpreted as children so this is probably correct – at least for Bristol.

The Children

We know the birth year of at least four of the sons and several of the girls.

John was born in 1600, and not 1590 as shown elsewhere [i], Christopher in 1612, Thomas in 1614 and Samuel the following year, but the dates of birth for some of the other children is uncertain.

The order of the girls and most of the boys is know, as well as all the names of those who were alive in 1619, except for one son, possibly Robert, if we assume 6 sons and John.

Daughter Joyce married in 1624 and a daughter, Anne, was born a year later – so must have been at least 18 and puts her birth as 1606 or earlier, and she is the 6th daughter which makes a lot of the girls older than most of the boys.

The girls were all left varying amounts in the will for their marriages in specific order of age – there is no mention of twins unless these are Elizabeth and Anne, but then Elizabeth is identified as the eldest.

Daughters Frances and Susan were both born in Shrivenham, Berkshire before eldest son John, so Elizabeth and Anne were also born before 1600.

Daughters Frances and Susan were both born in Shrivenham, Berkshire before eldest son John, so Elizabeth and Anne were also born before 1600.

1. Elizabeth £200

2. Anne £200 – died before marriage

3. Frances £100 [ii]

4. Susan £200

5. Dorothie £200 – died before marriage

6. Joyce £200

7. Marye £300 [iii]

[i] The matriculation date for John is incorrect in the transcribed Oxford records by 10 years, which makes his birth 5 years before his parents were married – he was actually born in 1600.

[ii] Robert was worried that Frances was going to marry someone “unsuitable” [which she apparently did] so held back some of her inheritance.

[iii] Mary was to be paid from money due on the death of Margaret Capell the mother of Katherine Stocker, wife of John the eldest son.

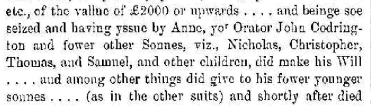

The precise order of the boys cannot be identified from the will so we have to wait until the court proceedings of 1627.

William was named specifically in a court case regarding his apprenticeship and payments made by his Mother.

Codrington V Marshe 1627

The case of [William] Codrington v Marshe is interesting as it not only gives us an idea of William’s age, but also includes information about the will from Anne herself.

William trained as a clerk for 5 years but Anne paid for his education for a year and three-quarters after the death of Robert. If he started his apprenticeship [at about age 16] then his apprenticeship began in 1620 and he was born about 1604.

The case was heard in December 1627, after William had completed his apprenticeship and was a clerk of the court in London. After this case William himself is not named again, so either his claim was no longer relevant to other cases or he had died.

In the evidence given by Anne it is specified that, at his death, Robert only had 7 daughters and not 8, and he also gave £10 each to his younger sons.

He also gave the lease of certain woods to his eldest son John, on condition he pay £20 each to the six sons of Robert – “… to Robert Codrington his six sonnes £20 apiece … “

Codrington V Marshe 1628

This case was brought by: John Codrington, Nicholas Codrington, Christopher Codrington, Thomas Codrington, Samuel Codrington, Edward Ernley and Frances his wife, Christopher Terry and Elizabeth, his wife, Susan Codrington and Mary Codrington.

Joyce is also mentioned later as a complainant along with husband James Prynne.

Basically this is all the family members, and their partners, other than sons William and Robert.

Why these two are not included can be interpreted in several ways: either they were dead or had no legal claims – they were the two oldest boys, other than John.

However at the time of Robert’s death they would probably have still been in education – being 16 or younger – and any issues with inheritance should have included these two boys.

Anne and another sister Dorothy had both died since the death of Robert, but before they “intermarried”, leaving their inheritance to be divided among the remaining sisters.

The inheritance left to the girls was an amount to be paid on marriage and because neither had married their deaths were relevant to this case, however this seems not to be the case for the unmentioned William and Robert who had been paid an allowance only during their period of education and training.

If we assume that the record for Robert from the Oxford records is correct, and that he was the second son it is possible he died before this case in 1628 – I can see no reason why he should not be named in at least one of the cases as had brother William.

If he was the son of this Robert then he would not have been at Oxford when his father died and would still have been receiving financial support, so he should have been included.

These are the approximate birth dates for the children – Robert and Anne married in 1595.

Elizabeth 1596?

Anne 1596?

Francis 1597 Shrivenham

Susan 1598 Shrivenham

John 1600 (from will of Simon Codrington)

Robert 1602?

William 1604 (if 16 when he was apprenticed)

Dorothy 1607?

Joyce 1608

Nicholas 1610?

Christopher 1612 [i]

Thomas 1614 [i]

Samuel 1615 [i]

Mary 1618?

[i] Records are available for St. Augustine’s, Bristol as Cotherington.

John

John was the eldest son, born in 1600.

In the 1630 chancery case John is shown as “of Wrington” in North Somerset.

He was High Sheriff of Gloucestershire in 1638 and Deputy Lieutenant in 1642.

He was also the heir to his grandfather Simon, who outlived his father Robert by some considerable time.

In 1643 he was appointed to the committee of Sequestrators of the Estates of Delinquents and in 1660 signed an address of welcome for Charles II after the restoration, and seems to have come through the civil war without too many problems.

He was married three times and inherited a lot of land in North Somerset, in particular from his third marriage to Frances Guise.

1. Katherine Stocker (1611-1629) married 1617

Katherine was the daughter of Margaret Capell from her marriage to Anthony Stocker and, according to the dates, was only 6 when she was married.

Katherine and John had one daughter, Ann, born in 1629, when Katherine would have been 18 but she died the same year either in child-birth or from complications.

After the death of her husband Anthony, Margaret married a cousin, William, thus changing her name back to Capell. [I wish they wouldn’t do that]

2. Anne Still (1613-1635) married 1632

They had a daughter Jane who married Samuel Codrington of Dodington.

3. Frances Guise (1626-1676) married 1647

Son and heir Robert was born 1649

During the civil war John was involved in the raising a militia to protect the cities of Gloucester and Bristol from royalist forces.

He and his cousin Samuel of Dodington were also on several important committees but managed to avoid any implications following the restoration of the monarchy.

John died in 1670 at the age of 70 – confirming his birth as 1600 and not 1590, as suggested elsewhere – and was buried in Wapley church, Gloucestershire.

Here lyeth the Body of John Codrington,

of Codrington, Esq. Who departed this Life

the 25 day of September Anno Dom’ 1670

aged seventy years.

Robert

Assuming that the mention of “six younger sonnes” in the will does not include eldest son John, then one of the sons of Robert and Anne is unidentified, and this could be Robert – why would Robert not have a son called Robert?

Robert is referenced in the records of Oxford university as matriculating in 1621 at the age of 19, putting his birth as 1602 – RHC assigns him to this family as A14.

But this record probably refers to Robert, son of Richard Codrington of Dodington who also went to Oxford – and we have additional evidence of this in a court case.

It is possible that the Oxford records may have merged two Roberts – they would have been there at the same time – but crucially only one finished their degree, and there is only one record for a Robert at this time.

Robert, son of Robert, is not named in the will or in any of the chancery proceedings, so it appears he was dead by 1627 or at least he was old enough not to have been involved in any of the court cases.

In one interpretation of the will, Robert A11, identifies six younger sons and his eldest John, making 7 sons, so one son seems to be missing and it is assumed that this is Robert.

Another interpretation is that there are only six sons including John.

But more importantly in court cases from 1627 to 1630 the other sons of Robert who were alive at the time are named.

“Ye Orator John Codrington and fewer other sonnes, viz., Nicholas, Christopher, Thomas and Samuel and other children …”

This names John, four other sons and with William (who was alive in 1627) this makes six.

It seems that Robert may never have existed, or he died in infancy, so the frieze could actually include Robert and Anne and their 15 children, with Robert possibly as the prone male figure and one unknown female.

But this is not certain and there is no single piece of evidence to say whether Robert existed or not.

See [I,Robert] for more information.

Nicholas

Nicholas appears in the records of Sir Edward Seymore’s Regiment of Foot as Lieut. Colonel Nicholas Codrington during the civil war.

Royalist regiment of foot serving with Prince Maurice’s forces in the West Country, then in garrison at Dartmouth

1643 October: Taking of Dartmouth

1644 April to June: Siege of Lyme Regis

1646 January: Besieged at Dartmouth

During the civil war he was based in Dartmouth in Devon and a daughter was born there, Kateren, which is also the name of his wife.

After being captured following the siege of Dartmouth he was listed in the records of the mayor as Lt. Col. Codrington, and this record has been assigned incorrectly to other members of the family, specifically brothers John and Christopher.

Before the Civil war he served in the army of King Charles I during his Northern Expedition – arrears for his pay were recorded in parliament July 1642, having been missed from a previous submission.

Codrington’s &c. Arrears.

Ordered, That the Names of Captain Nich. Codrington and Captain Bainton be inserted into the Order made for the Pay of divers Officers on Saturday last; and that the Arrears of their personal Entertainment, for their Service in the late Northern Expedition, appearing to be due unto them upon Sir Wm. Uvedale’s Certificate, be paid unto them out of the Monies that come in upon the Bill of Four hundred thousand Pounds, in the like Manner as those Officers were ordered on Saturday to receive their Arrears.

He had died by 1665 as his widow Katherine made a claim for herself and daughter Penelope.

1665: Katherine, widow of Col. Nicholas Codrington, and Penelope, their daughter. For a pension or other relief; the late colonel lost 3,000 by his loyalty, and they are reduced to great want, and have received nothing from the 60,000l. for indigent officers, nor the 9,000l. for their widows.

Certificate by Sir Edw. Seymour, and six others, of Col. Nich. Codrington’s services, both before and after the Restoration.

The identity of his wife, Katherine, is not known.

William

William trained as a clerk in a 5 year apprenticeship under John Scharburgh of London, which started in about 1620 – his mother had paid for his schooling after the death of his father – in early 1619 – for one and three-quarter years.

The apprenticeship was secured by his brother-in-law Christopher Terry – husband of Elizabeth – who was apprentice before him.

William had completed his training and was now a clerk of the court in London, but because his mother had paid for him during this period it appears he was denied the £10 quarterly mentioned in the will of his father.

If he started his training in 1620 then he must have been about 16 and born about 1604.

He was alive in 1627 when the court case provided much of this information, but nothing is known after this time and he is not mentioned in other court cases, which may just be because his case had been resolved.

Recently I can across a record in a book regarding William Coddington who subscribed to the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629 – he was also Treasurer – and went there with the first voyage in 1630.

He was governor of Newport in 1640 and governor of Rhode Island in 1678, the same year he died.

All the pieces about his life seem to fit with this William – his date of birth, a good education and his involvement with the law.

But the name is spelled differently and there are reports of him coming from Boston in Lincolnshire, son of a Robert Coddington who died 1615.

Dictionary of British America, 1584-1783 By Mary K. Geiter, W.A. Speck

Rather a coincidence though … and the evidence of being born in Lincoln is rather thin.

Certainly William lived in Lincolnshire and had friends there – in particular John Cotton, a clerk (minister) who emigrated to Boston later, but there is no evidence of him corresponding with any members of his family other than a mention of a cousin who may have been a relation of his first wife, Mary.

Robert Codrington 1574-1618

William Codrington 1604-????

Robert Coddington 1575-1615

William Coddington 1601-1678

Perhaps he had abandoned his family in Gloucestershire for Lincolnshire, started a new life and then moved to America – the name change may have been a mistake?

William also had a son, Thomas born 1655 but this seems to be a little too late to have been the Sheriff of New York – as suggested elsewhere [see Thomas below] – but if this is the case then the name had reverted to Codrington, providing further confusion.

William has also been linked to the Coddington family of Dorking, Surrey who emigrated to Boston, but there is no evidence he is related.

There are many different ways of spelling Codrington, and at this time it was far from standardised. Robert, the father of William, signed his will as Coderingtonne and Cotherington is also quite common.

There are many different ways of spelling Codrington, and at this time it was far from standardised. Robert, the father of William, signed his will as Coderingtonne and Cotherington is also quite common.

But the key to the name is the R in the middle: all the accepted variations have this and a change to Coddington without an R – which significantly changes the way it sounds – could hardly be a simple mistake.

Boston Connection

William Coddington was first married [Mary Burt?] in Boston, Lincolnshire 1626 where his friend John Cotton lived.

His second marriage to Mary Moseley was in Essex 1631 so he did not return to Lincolnshire when looking for a second wife – John Cotton had already moved to Massachusetts by then.

He also had a third wife Anne Brinley with whom he had seven children between 1651 and 1663

Christopher

Much has been written about Christopher, although there is some confusion between Christopher, his son and grandson both named Christopher.

Christopher I (1612-1656)

Christopher II (1640-1698)

Christopher III (1668-1710)

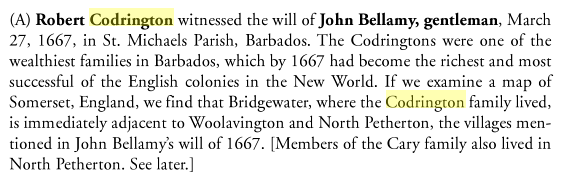

It is not known how, or exactly when, Christopher I ended up in Barbados.

There is no evidence for anything he did while in England and it seems he left about 1630, so would have only been 18. His father had died in 1619 and his grandfather, Simon, in 1631, so perhaps this was the trigger for him leaving?

Possibly he was following the example of his great uncle John and was heading for Virginia – his father and grandfather were both members of the Virginia Company [although this had failed by 1624 when Virginia became a Royal colony] – but saw opportunities in the sugar plantations of the Caribbean and stayed in Barbados, marrying the sister of Sir James Drax in about 1638.

The journey to Virginia may have been on one of the ships making the triangular trip from Bristol to the Caribbean, on to Virginia and then back to Bristol following the trade winds.

The Drax family had pioneered the techniques for growing sugar in Barbados and were already influential on the island and Christopher would no doubt have been in contact with them if he stopped over in Barbados.

… James Drax, the first sugar baron, who introduced sugar cultivation to Barbados, as well as extensive slavery; the Codringtons, the most powerful family in the Leeward Islands, who struggled to fashion a workable society in the Caribbean but in the end succumbed to corruption and decadence …

See The Sugar Barons by Matthew Parker

Samuel

Samuel was baptised in St Augustine’s church in Bristol 19 Sep 1615 which makes him the youngest son, and confirms the naming sequence used in court records.

The only reference to him I can find is a possible link to the Stradling family in Somerset, but this may have been one of the other Samuels from the Dodington branch of the family who moved to Somerset after selling Dodington to Christopher Codrington in about 1700.

A Samuel is shown in the genealogy of Oliver Cromwell as marrying Elizabeth Oyle, but this is probably too late and he also seems to be a member of the Dodington family.

Possibly Samuel was killed in the civil war or outbreak of plague or just had an uneventful life.

He is mentioned in the will of his cousin Thomas Tatton in 1643 so was still alive then.

Thomas

It was probably this Thomas that worked for the East India Company in Surat, India.

It seems he was based in Isfahan, Armenia and, at one point, married an Armenian woman and was dismissed.

A Court of Committees, January ai, 1648 {Court Book, vol. XX, p. 194).

A letter is read from Thomas Codrington, who served as a factor in India for thirteen years, but having married an Armenian woman was dismissed from the Companys service; he desires to be re entertained and that what is due upon his account may be paid to Nathaniel Teemes ; because of his long service his request is granted, and as he knows Persian he is entertained for the Customhouse at Gombroon at 60/. per annum, subject to the approval of the President and Council at Surat.

Thomas was the second youngest son of Robert and Anne born in 1614, so would have been 34 when this letter was written and 20 when he started working for the company as a factor.

Feb 26 1634

Sureties accepted for several Factors, viz., for Tho. Leyning, Peter Eldred, grocer; for Edward Pearce, his father water bailiff of the city; for Philip Vaughan, Hugh Day, cooper; and for Tho. Codrington, Mr. Prynn, late Under Sheriff for Middlesex.

His sister Joyce, was married to James Prynne, so perhaps his father or another relative stood surety for Thomas.

1633 East India Company Court Minutes

Salaries conferred by the balloting box on other Factors, viz., Guy Bath and James Corbett, 50l. per annum for five years; John Wild and Philip Vaughan, 40l. and 10l. yearly rising for seven years; George Wetherell, Thomas Leynyng, Henry Chapman, and Wm. Smethwyke, 20l. and 10l. yearly rising for seven years; Samuel Boyce, Thomas Adler, Wm. Pitt, and John Vickris, 30l. and 10l. yearly rising for seven years; Ambrose Taylor and Philip Saunders, 40l. per annum for the first three years, and 50l. per annum for the other four years; and Thomas Codrington entertained apprentice for seven years at 20l. per annum, to be allowed 10l. thereof yearly in the country.

Nov 13 Thomas Codrington Employment as Faetor [factor]

Later he is also referenced as a merchant in relation to some art:

Copy, in the hand of the English merchant Thomas Codrington, 20 September 1637. In an album compiled by the interpreter to the German legation of the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein to the court of Shah Sefi I in Isfahan, Persia. 1637.

I do not know what happened to Thomas after he was reinstated in 1648 but in the above reference he is shown as a merchant, unless this is a different Thomas.

Captain Thomas Codrington, merchant, was sheriff of New York in 1691 and bought land in Somerset County.

It is possible that this is our Thomas but I think it unlikely – he would have been about 55 at the time he first purchased land in 1681, and died in 1710 so would have been 95.

See Thomas Codrington, Sheriff of New York.

Daughters

There is no mention of twins in the will but they are shown as the second female figure on the memorial.

But recently I have found separate birth records for sisters Frances and Susan [Cotherington] in Shrivenham, Berkshire [where their parents were married] which makes it more than likely that Elizabeth and Anne were the twins and referred to as the two eldest daughters.

There is simply not enough time between the marriage of Robert Codrington and Anne Stubbes in May 1595, and the birth of Frances in October 1597 for there to be two additional births.

This means that Elizabeth and Anne must be the twins and that the main female figure must therefore also be Anne and not any of her daughters – and more than likely this makes the main male figure Robert and not eldest son John.

Elizabeth

According to the will, Elizabeth was the eldest daughter and may have been one of twins, with Anne.

She was probably born 1596 – younger sister Frances was born 1597 – and married in 1620 to Christopher Terry, a law clerk at about the age of 24.

The only close record for Christopher Terry is a baptism in Dorking Surrey, 1605, which seems a little late as he would be significantly younger than his wife.

I can find no other records for either Christopher or Elizabeth Terry and only one birth – an unnamed child registered to Christopher Terry in 1636 – the child probably died in infancy.

There is a death record for Elizabeth Terry in 1660 at St. Dunstan’s in London, the same church as the dead child but I can find no other records of children.

As Christopher was a clerk of the courts in London St. Dunstan’s is a reasonable location for the family to have lived.

Anne

Anne was born about 1596 and died shortly after her father in about 1620.

She may have been a twin with sister Elizabeth, although she is shown as the second daughter in the will of father Robert.

Frances

Frances was the third daughter born in Shrivenham, Berkshire 1597

Sep 16 COTHERINGTON Frauncys d Robte

She married Edward Earnley, against her father’s wishes and he left only £100 in his will to Frances, instead of the £200 left to his other daughters, in anticipation of this.

But it seems he was correct as there were some problems with this marriage as recorded in the chancery court records 2nd Aug 1628

… after the intermarriage of Frances defendant [Anne] p’ceived the unkinde and sep’ate living of the said Edward Earnley …

At one point Frances returned home to her mother and Anne deposited £100 with elder son John in order to maintain Frances with the promise that the couple would get the money if they should “live together as man and wife oughte to doe … “

Edward was not to get his hands on the money unless they were a couple:

… but if Frances should dye during such sep’ation from her husband the £100 to be equally divided among the surviving sisters of Frances …

Frances Earnley is mentioned in the will of her cousin Thomas Tatton in 1643, so she was probably still married to Edward at the time.

Susan

She was born in Shrivenham, Berkshire 1598 and died unmarried in 1628 at the age of about 30.

Oct 8 COTHERINGTON Susan d Robte

Dorothie

She died before marriage – probably before 1627

Joyce

Married James Pryn and they had at least two daughters, but Joyce died before she was 30.

I have not found out what happened to the children, but it is likely that James remarried.

A member of the Pryn family stood surety for her brother Thomas when he started working for the East India company.

Marye

I can find no record of what happened to Mary the youngest daughter.

References

[RHC] Robert Henry Codrington.

[RHC] Robert Henry Codrington.

Robert Henry Codrington wrote two invaluable documents about the Codrington family.

These were published by the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society and are include in the references below.

Without these documents the Codrington side of the family would have been a complete mystery.

[1] Bristol Cathedral Heraldry

by F. Were

1902, Vol. 25, 102-132

http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v025/bg025102.pdf

[2] Memoir of the Family of Codrington of Codrington, Didmarton,Frampton-On-Severn, and Dodington

by R. H. Codrington

1898, Vol. 21, 301-345

http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v021/bg021301.pdf

[3] A Family Connection of the Codrington Family in the 17th Century

by H. R. Codrington [RH on inside cover]

1893-94, Vol. 18, 134-141

http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v018/bg018134.pdf

[4] Effigies of Bristol

by I. M. Roper

1903, Vol. 26, 215-287

http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v026/bg026215.pdf

[5] The history of the island of Antigua

V. Langford Oliver

The author has collected together a number of records which have been extremely useful – wills, court cases and pedigrees – essentially about the Codringtons of Barbados, but also including some of the previous generations.

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tEUIAwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&hl=en&output=reader&pg=GBS.PA167

Notes

Anything shown in [square brackets], other than the numbered references above, is a comment or note by me rather than the original author.

Not all the references shown above are used in this document but will be used in others about the Codrington family and have been included so I can keep the reference numbers the same.

Chris Sidney 2014

Recent Comments