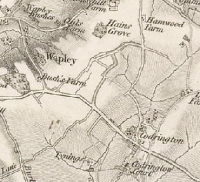

John Codrington died on 9th October 1475. This date is engraved on his tomb in St. Peter’s church in Wapley, Gloucestershire along with his age – 111 years, 5 months and 13 days.

John Codrington died on 9th October 1475. This date is engraved on his tomb in St. Peter’s church in Wapley, Gloucestershire along with his age – 111 years, 5 months and 13 days.

I have removed some parts of this article because it was getting much too long. My thoughts on the grant of arms to John Codrington and associated information can now be be found in The Codrington Arms although some references are included below where they are relevant to this article.

Eleventy One, as Bilbo Baggins said at his birthday party, is a great age and extremely unusual – even today – so could John Codrington really have beaten the odds and reach this grand age in the 15th century?

RHC in his “Memoirs of the Codrington family” [see below] calculated the birth of John Codrington as 23rd April 1364 from his age and the date that he died, which are both recorded on his tomb.

The age being recorded so precisely is quite unusual, suggesting that it was, indeed, exceptional. But one hundred and eleven?

The age being recorded so precisely is quite unusual, suggesting that it was, indeed, exceptional. But one hundred and eleven?

One suggestion is that the stonemasons made an error with the Roman numerals – or the instructions they were given were incorrect – and the age on the tomb should be 91 XCI instead of 111 CXI, but even this age is noteworthy.

Of the six possible combinations of the roman numerals on the tomb, only three are valid: CXI = 111, CIX = 109, XCI = 91 and the most obvious error is to swap the first two characters.

If true then the date of his birth should be 26th April 1384.

RHC had himself seen the inscription in 1852 and was convinced that it had not been tampered with but he had no way of knowing if it was actually correct to begin with and took the age at face value.

Here lies Johannes Codry’ton knight, who died on the ninth day of the month of November in the year of our Lord 1475, having the age on the day that he died of 111 years, 5 months 13 days, may God bless his soul. Amen

If the lower age is correct then this would help to clarify some aspects of the life of John Codrington. For a start he would have been 20 years younger during Agincourt at the age of 30, and would have also married at a more sensible age.

But it opens up other issues, in particular about his father, Robert, who would have been quite an old man when John was born, and whether there are any missing generations.

This article is based largely on the definitive work on the Codrington family by Robert Henry Codrington [RHC] – the snappily titled “Memoir of the Family of Codrington of Codrington, Didmarton, Frampton-On-Severn and Dodington.” – which was itself based on notes made by the historian, Sir John Maclean.

This article is based largely on the definitive work on the Codrington family by Robert Henry Codrington [RHC] – the snappily titled “Memoir of the Family of Codrington of Codrington, Didmarton, Frampton-On-Severn and Dodington.” – which was itself based on notes made by the historian, Sir John Maclean.

Sir John had intended to follow up on his Memoirs of the Poyntz and Guise families – who are related to the Codringtons through various marriages – but illness prevented him from doing so.

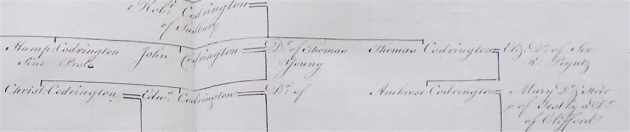

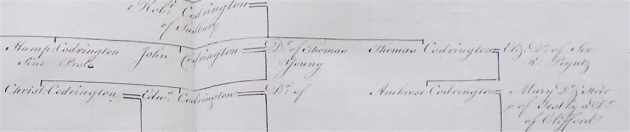

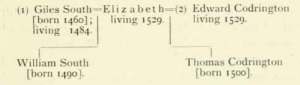

In his document, Robert identifies John Codrington as A1; the head of the senior branch of the Codrington family and his brother Thomas as B2; the head of the junior branch.

Robert also says that:

John returned from France and married a young woman, survived his son, and died in extreme old age.

But I don’t think it is as simple as that.

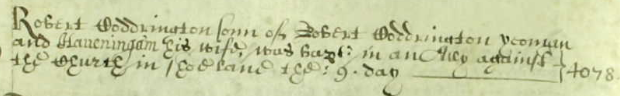

Robert Codrington

John’s father was, according to all know pedigrees, Robert Codrington of Chipping Sodbury in Gloucestershire, who “was in good standing” during the reign of Henry IV.

He appears in several jury records around the end of the 14th century – with various spellings of his name. The last record we have for him is when he appeared on a jury list at Chipping Sodbury 20 May 1421.

Some have assumed that this date was when John inherited the Codrington property, but was it from Robert and was it some time later than 1421.

The first reference to John in relation to the property seems to be in 1429 when he and his wife made an application to the pope for a portable altar, so all we can say for sure was that he inherited the property, and married, before this date.

Why was Robert never described as being of Codrington and Wapley? Could it be that Robert was not, after all, the father of John?

John Codrington is remembered as the Standard Bearer for King Henry V at the battle of Agincourt as described elsewhere.

It should be noted that John Codrington was never knighted for his service and references to Sir John Codrington seem to have originated with a number of military figurines, as well as various books about Agincourt one of which has him pictured on the front cover and labelled inside as Sir John.

On his tomb he is referred to as Joh’es Codry’ton armiger, which only means that he has the right to bear arms. In a document of 1471 he is John Codrington Esquire and this is confirmed by the way the helmet is shown on the family crest, at an angle and not facing forward.

On his tomb he is referred to as Joh’es Codry’ton armiger, which only means that he has the right to bear arms. In a document of 1471 he is John Codrington Esquire and this is confirmed by the way the helmet is shown on the family crest, at an angle and not facing forward.

It is easy to see why you might assume that he was knighted, being standard bearer to the king, and I am as guilty as anyone of repeating this without checking if it is actually correct.

RHC does not make this mistake and he is referred to as either gentleman or esquire, although I am unsure at what point he was able to use this later address.

Possibly the title is related to when he became lord of the manor of Codrington, after purchasing it from the abbey of Stanleigh in 1455.

It is also possible that this was a title used when addressing him formally, simply because he was a knight, rather than having been knighted – we still sent letters these days starting “Dear Sir“.

It has been suggested that John Codrington may have been knighted on the battlefield, or by someone other than the king.

At Agincourt he was in the retinue of Sir William Bourchier. who was probably senior enough to have been able to do this.

Sir William Bourchier, was one of the foremost captains at the Battle of Agincourt, leading 102 men. In November 1415 he was made Constable of the Tower of London (replacing the Duke of York, who had died in the Battle), with special responsibility for the French prisoners. He returned to serve in France in 1417, and in 1419 was made Count of Eu in Normandy. His arms were those of Bourchier quartered with those of Louvaine (the arms of his mother, an heraldic heiress).

But if John was knighted for his services there is no evidence of the title ever being used.

In 1429 John is a layman of the diocese – in the request for a portable altar – and in 1441 an 1445 grants of arms he is a Gentleman. It is only in the 1471 Levy of Fines that he is referenced as Esquire, technically the rank below knight.

In the list of the retinue of William Bourchier John is well down the list of men at arms, showing that he was – at that time at least – not particularly important.

He is also shown in some accounts as John Codington so perhaps Symon Codington, in the retinue of Lord Camoys, was related?

Two Wives

There are two different wives suggested for John in “memoirs”, both named Alice.

She could have been Alice Young, daughter of Thomas Young, an influential Bristol merchant, or Alice Hawys the sister of Margaret, who was married to Sir Peter Bessiles.

The name of Hawys has been transcribed as Hannys orHauuys and also shown as Hewes and Hawes.

It has proved difficult to find connections to these families at about the right time. What we do know is that Alice survived her husband – and two of her sons – and so I have come to the conclusion that John probably had two wives, perhaps both named Alice.

Why wouldn’t he? Some men have two or three wives in a much shorter lifetime.

In some family records Margaret (Margerie) Hawes married Sir Peter Bessiles, of Bessiles Leigh, Berkshire in about 1389, so it would seem that John could have married her sister at about the same time – certainly before Agincourt.

The following is commonly used in other trees.

Peter DE BESSILES was born in 1364 in Bromland, Somersetshire, England. Parents: Thomas DE BESSILES and Katherine LEIGH.

Margery HANNYS and Peter DE BESSILES were married about 1389 in Besiles Leigh Berkshire England.

John Codrington and first wife Alice may have had a daughter, Margaret, who married Sir John le Veale, but the timings only work with a marriage some time before Agincourt.

JOHN (Johannes) VELE (Veal), son of Thomas and Hawise Veal, married MARGARET, and he died in 1430, the 9th year of the reign of Henry VI, leaving one son. [1]

[1] There may have been a son, John, born about 1405, as well as daughter Susan, born 1409.

Another possibility is that Margaret was a younger sister to John Codrington rather than a daughter, which could also work in this scenario.

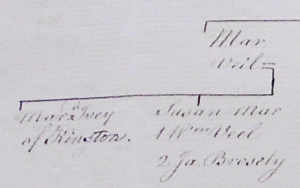

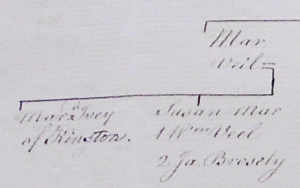

A Codrington pedigree held by the College of Arms shows only Mar and Viel, which some have taken to refer to a son Morvail Codrington, but is more likely to be an abbreviation of Margaret or could simply be an abbreviation for Married, where the name of a daughter is not known, or not recorded, to someone named Veil.

But this scenario does not fit with some other records that show that Margery Hawys married Peter Bessiles a generation later.

More importantly she is mentioned in documents dating from 1470 as the widow of Peter so must have been much younger and probably married much later than 1389.

Her sister, Alice, is therefore unlikely to be the first wife of John Codrington I.

One other problem with this theory is that there is a record for one Alice Hawes married to Henry Bromley in 1390, with an estimated birth date for Alice about 1365.

One other problem with this theory is that there is a record for one Alice Hawes married to Henry Bromley in 1390, with an estimated birth date for Alice about 1365.

This clashes with the estimated birth of John’s first wife who must have been born about the same time in order to have a daughter, Margaret, born about 1385.

Alice Hawys, who married John Codrington, was probably the niece of this Alice assuming they are both related to John Hawes of Solihull.

According to RHC the daughter of Margaret and John le Veale, Susan, married firstly James Berkeley of Bradley and, secondly, Richard Ivy of Kingston.

Margaret [Codrington] had died in 1409 after the birth of daughter, Susan.

John Codrington A1 (1364) = Alice I

.. Margaret Codrington (1390-1409) = John la Veele (1384-1430)

…. Susan le Veele (1409-)

There are some differences in the College of Arms pedigree as the name of husband James, is shown as Broseley, and it was an un-named sister of Susan that married [Richard] Ivey of Kingston.

Another pedigree – that of Samson Samuel Lloyd esq., who is descended from the Berkeley family – shows Susan as the widow of one Waddall adding even more confusion.

So perhaps it was a sister of Susan that married Richard Ivye? Richard is likely to have come from (Chipping) Sodbury in Gloucestershire and it was later generations of the family that lived at West Kingston in Wiltshire.

There are also suggestions, from other family trees, that Sir Peter Bessiles was born about 1390, and having looked into his pedigree the later date does fit better with other family records and with those of Margaret and Susan.

There are also suggestions, from other family trees, that Sir Peter Bessiles was born about 1390, and having looked into his pedigree the later date does fit better with other family records and with those of Margaret and Susan.

It is perhaps more likely that he simply married much later in life than estimated and it was his wife, Margery Hawys, that was from a later generation, with about 25 years difference between them.

In this scenario it seems as if John’s first wife was another Alice, possibly Alice Young – the daughter or [more likely] sister of Thomas Young – with whom he had a daughter, Margaret, who married John la Veale – assuming that this marriage is correct.

Thomas Young was about the same age as John Codrington and did have a sister [either Alice or Mary] who he could have married. If she was a daughter of Thomas then she would have been born a generation later which doesn’t work with a grand-daughter, Susan la Veele, born in 1409.

In this scenario John Codrington married again, after the death of his first wife, to Alice Hawys, the sister of Margery (widow of Sir Peter Bessiles), and had three sons; Humphrey, John and Thomas.

This makes it possible for Margery Hawys – born later than suggested above – to be mentioned in the Levy of Fines of 1470 [see below] without having been more than 100 years old.

Mind the Gap

I have wondered why there was such a gap after John returned from Agincourt before he married. The simply answer could be that he was already married, and at the age of 50 he probably had no plans to marry again – even when his wife died.

I have wondered why there was such a gap after John returned from Agincourt before he married. The simply answer could be that he was already married, and at the age of 50 he probably had no plans to marry again – even when his wife died.

We do not know how long John was in the service to the king after Agincourt and he may have returned to France for the campaign that began in 1417, and may even have made it to Paris, where Henry V died five years later in 1422.

If he was 50 years old during Agincourt then I doubt he would have been able to sustain a prolonged campaign. However if he was 20 years younger then he could have been with the king for a significant period, and this is perhaps why he is not recorded back in Gloucestershire until some time later.

Certainly he was back home and living in Codrington by 1429 – when he applied for a portable altar – but that is really all we can tell for sure.

John could have been about 65 and perhaps either he, or his wife, were unable to attend their local church easily and wanted to perform mass at home.

But this may also have been, as suggested by RHC, to avoid paying fees at nearby Wapley for his household.

… to John Codrington, layman of the diocese of Worcester, and to his wife then being …

John, although he didn’t know it, had another 50 years to live, and it is possible that he started looking around for another wife.

Based on the death of second wife Alice II, in 1489, she was probably born about 1415 and married John Codrington about 1435 – shortly after the death of his first wife – and their three sons were then born between 1435 and 1440.

This is quite late for John to have fathered three sons – he would have been in his sixties – and although not impossible it is just one more thing that doesn’t sit right with me.

The period when the boys are likely to have been born can be calculated by working backwards from the birth of grandson and heir, Christopher, in 1467 and assuming that his father, John, was about 30 years old when he married, putting his birth at about 1437.

We are now 20 years after Agincourt and John Codrington was already an old man, but there is an alternative to this that allows it bit more flexibility with the dates.

John Codrington and first wife, Alice, could have had a son … also called John.

John II

John II would have been born about 1390, a sister to Margaret, and may have been too young to accompany his father to Agincourt.

He could have been married to Alice II by 1425 and their sons born earlier than I have already estimated, which makes it easier to explain how two of them had died before their mother.

Grandson and heir Christopher Codrington would therefore have been born when his father, John III, was about 40.

John I may have transferred the Codrington estate to his son John II and his wife before 1471 even though he lived for some time afterwards, and any references to Alice and John regarding the property are for his son and his wife.

In the Levy of Fines from 1471 John is referred to as John Codrington Esquire, which is the correct address for John I, but could also be used for his eldest son as shown in the same document for eldest son Humphrey.

And afterwards the day after All Souls, 49 Henry VI [3 November 1471]. Parties: William Bolaker and Philip Parker, querents, and John Codrynton’, esquire, and Alice, his wife, deforciant.

John II would himself have been an old man of about 80 by his time and probably died before his father.

Humphrey, his eldest son, was Escheator for Gloucestershire in 1467, a position that demanded a certain amount of respect and probably not a position for a young man, but he could still have been born about 1435.

Grant of Arms

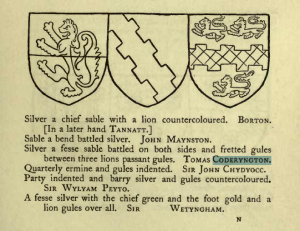

There were two grants of arms to John Codrington in 1441 and 1445 – the first being a confirmation of the arms used by John during his service to the king, as used by the senior branch of the family.

There were two grants of arms to John Codrington in 1441 and 1445 – the first being a confirmation of the arms used by John during his service to the king, as used by the senior branch of the family.

Whether these two grants were to the same John Codrington is discussed in The Codrington Arms, but there is some evidence that there may be another John Codrington in Gloucestershire at the time who could have been granted the second arms.

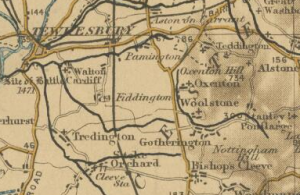

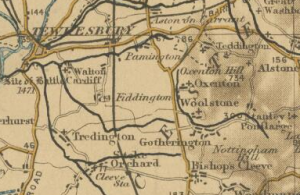

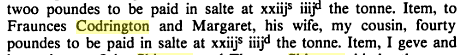

This John Codrington resided in Clyfe [Bishop’s Cleeve] near Tewkesbury, in the north of Gloucestershire and is recorded there in 1421 and of Tewkesbury in 1423.

Could John Codrington have lived in Tewkesbury after Agincourt but before inheriting Codrington and Wapley from his father, or is this another John?

One indication that this is a different John is that there was no mention – in the levy of fines of 1471 or the inquisition into the death of Alice Codrington – of any properties in the north of the county of Gloucestershire owned by the family.

There is an earlier record of a John Codrington from 1337, who was an attorney to the king and could be related to John Codrington of Clyfe and Tewkesbury.

See below for more information about him.

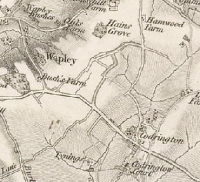

Wapley

The earliest reference linking the Codrington property to the family is for Stephen of Codrington and Wapley, who made a donation to Stanleigh Abbey – who owned the Codrington and Wapley manor – in 1379.

2 Ric. 2. receit. et confirm. donationes: P. 869. cart. antiq. X. n. 6, fcil. 2 Ric 2. confirm. donationem R. fil. Stephani de Codinton et Wapalee.

Possibly Stephen had died without an heir and passed Codrington to brother Robert, or directly to nephew John?

Or possibly it was Stephen who was father to John I and Robert was his younger brother which is why he never inherited the Codrington and Wapley properties and is described only as being of Chipping Sodbury?

RHC says that the two arms granted to John Codrington have only been used quartered together so perhaps there was a marriage between the two branches of the family and the second grant of arms was requested prior to a marriage between the families?

It is therefore possible that one of the children of John II could have married a cousin, the daughter of John Codrington of Clyfe. This would explain the quartering of the two designs and why they were never used in their own right if this second John had no sons.

Perhaps this was the marriage of Humphrey, the eldest son? If he married a cousin Agnes Codrington about 1445 – after the second grant of arms – he could have been born around 1425, fitting better with John II being his father.

There is no evidence of this of course; certainly there are no properties or lands held by the Codrington family in the north of Gloucestershire, either inherited or passed through marriage.

The only use of both arms I have found was 300 years later, and this may have been in error on the assumption that they were for the same John Codrington.

The only use of both arms I have found was 300 years later, and this may have been in error on the assumption that they were for the same John Codrington.

Having not seen the text of the actual grants – only extracts from them in various forms – I am not really in a position to do anything other than speculate as to whether they are for the same John based on other interpretations of the grants.

Levy of Fines

In 1471 John and Alice levied a fine on their lands to their sons, Humphrey, John and Thomas and this could have been either, John II and his wife Alice Hawes as mentioned earlier, or John I and his second wife.

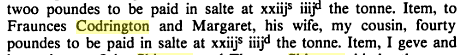

Also mentioned is Margery, late wife of Peter Bessiles, who was the sister of Alice II, with Peter Bessiles being born later than shown in some references – or at least marrying much later and Alice being much younger than he was.

William and Philip have granted to John and Alice the tenements and have rendered them to them in the court, to hold to John and Alice, without impeachment of waste, of the chief lords for the lives of John and Alice. And after the decease of John and Alice 2 messuages, 1 toft, 240 acres of land, 30 acres of meadow and 40 acres of pasture in the vills of Codrynton’ and Tormerton’ shall remain to Humphrey Codrynton’, esquire, son of John and Alice, and the heirs of his body, to hold of the chief lords for ever. In default of such heirs, successive remainders (1) to John Codrynton’, brother of the aforesaid Humphrey, and the heirs of his body, (2) to Thomas Codrynton’, brother of the same John, and the heirs of his body, (3) to the heirs of the bodies of the aforesaid John Codrynton’ and Alice, (4) to Margery Besiles, late the wife of Peter Besiles, knight, and the heirs of her body and (5) to the right heirs of Alice. And also after the decease of John Codrynton’ and Alice 5 messuages, 1 toft, 5 gardens, 60 acres of land, 40 acres of meadow and 40 acres of pasture in the vills of Oldesodbury, Chepyngsodbury, Lygrove and Dodyngton’ shall remain to the aforesaid John Codrynton’, son of John Codrynton’ and Alice, and the heirs of his body, to hold of the chief lords for ever. In default of such heirs, successive remainders (1) to the aforesaid Thomas, brother of the same John, and the heirs of his body, (2) to the aforesaid Humphrey, brother of the same Thomas, and the heirs of his body, (3) to the heirs of the bodies of the aforesaid John Codrynton’ and Alice, (4) to the aforesaid Margery Besiles and the heirs of her body and (5) to the right heirs of Alice. And besides after the decease of John Codryngton’ and Alice 6 messuages, 2 tofts, 1 garden, 1 dove-cot, 100 acres of land, 30 acres of meadow and 40 acres of pasture in the vills of Bristoll’, Leyghterton’, Haukesbury and Upton’ Hamell’ shall remain to the aforesaid Thomas, son of John Codrynton’ and Alice, and the heirs of his body, to hold of the chief lords for ever. In default of such heirs, successive remainders (1) to the aforesaid John Codrynton’, brother of the same Thomas, and the heirs of his body, (2) to the aforesaid Humphrey, brother of the same John, and the heirs of his body, (3) to the heirs of the bodies of the aforesaid John Codrynton’ and Alice, (4) to the aforesaid Margery Besiles and the heirs of her body and (5) to the right heirs of Alice.

According to RHC, Margaret Hawys, the widow of Peter Bessilles, Knight, died in 1483, making her a similar age to Alice who died a few years later. I have not found information anywhere else to confirm this date, but some pedigrees show Peter Bessilles being born in 1390 instead of 1364 making it much easier to estimate a later marriage. But even the earlier date does not mean he did not marry Margery – she would just have been much younger – a lot younger.

The inquisition into the death of Alice identifies Christopher Codrington as her heir.

“… aged 22 and more, is her cousin and heir, viz son of John, her son.”

Not quite sure why he isn’t just referred to as her grandson – the term cousin is usually used to indicate a close, but indirect, relationship.

Also mentioned in a deed dated 1490 are Thomas Codrington [assumed to be the youngest son], William Besylys, Christopher Twynyho, Clerk and William Twynyho, Esquire, which confirms that there were relationships between these families.

Christopher Codrington, heir of Alice, married into the Twynho family and William Bessiles was, no doubt, related to Alice and Margery.

I still think is a bit unusual to mention Margery Bessiles in the levy, unless she was actually a daughter of John and Alice and not the sister of Alice at all. But if she was the sister to Humphrey, John and Thomas she would have been born much to late to have been married to Peter Bessiles.

I still think is a bit unusual to mention Margery Bessiles in the levy, unless she was actually a daughter of John and Alice and not the sister of Alice at all. But if she was the sister to Humphrey, John and Thomas she would have been born much to late to have been married to Peter Bessiles.

According to records for the manor of Leigh, Margery and Peter Bessiles did not have any children, but other pedigrees show a son, Thomas, so what is going on?

Sir Peter was noted for his deeds of charity and his gifts to religious houses, and by his will he directed that all his manors should be sold by his co-feoffees in alms for his soul. He died childless in 1424 …

The history of the manor during the next few years is involved, because Sir Peter’s will was not very honestly performed. Margery, his widow, and one of the executors of his will, had a life interest in Leigh, and her second husband William Warbleton held it in her right in 1428.

Margery married again – before 1428 – to William Warbleton and died in 1483, so she was still young at the time she was widowed. Some records show a son, Thomas, born in 1390, but this is much too early – even if Margery lived to be 100 years old!

The History of Parliament adds some additional information which makes it easier to understand what is going on, in particular that Margery was the second wife of Peter Bessiles and that she also had an illegitimate son.

He left no immediate heirs, and Thomas, the illegitimate son of his second wife Margery Haines (who afterwards called himself Thomas Bessels and claimed to be Sir Peter’s son and heir), received no more by the terms of the will than a life interest in a small estate at Longworth together with the expenses of his education. Margery was permitted to keep the manors of Bessels Leigh and Kingston for her lifetime, but these were then to be sold.

As Margery lived until 1483 she cannot have been born before about 1400 and must have been very young when she gave birth and married to Peter. It seems that the marriage was a formal arrangement and, based on that, I would think that Thomas probably was the son of Peter Bessiles, otherwise why would he have married a young woman with an illegitimate son?

Eventually Margery managed to get some of the property for her son and his heirs, although it sounds as if Thomas had already died.

By outliving Sir Peter by nearly 50 years, the widow successfully contrived to have Radcot and Grafton entailed to the advantage of the issue of her bastard son Thomas.

Thomas married Clemence de Noires and their son, William, married into the important Harcourt family of Stanton Harcourt in Oxfordshire, so illegitimacy hadn’t done him much harm.

In the Levy of Fines document of 1471 Margery is still shown as the widow of Peter Bessiles and not the widow of William Warbleton who died 1469, which is quite odd.

Also if Margery was Haines and not Hawys then the wife of John Codrington must also be Alice Haines and calls for some further investigation.

Margery’s legitimate heir was her nephew, John Haines of Salop.

Probably, however, this name was assumed from the name of her nephew, who may be the son of another sister who married into the Haines family.

Three generation later Dorothy Fettiplace, great grand-daughter of Thomas Bessiles, married John Codrington, the eldest son of Christopher Codrington (great-grandson of John of Agincourt) but he died in Appleton, Berkshire in 1518 and Dorothy ended her days in the Abbey of Syon along with two of her sisters.

Humphrey

Humphrey is a bit of an enigma. It appears – from some records – that he was significantly older than his brother John III, the father of Christopher [who inherited the Codrington property] and died without any children, although it is possible that he was married.

There are chancery records dated 1431-1443 for Humphrey meaning that he would have been born significantly earlier then 1435, especially as these dates relate to his position of escheator.

He could therefore have been a brother to John II or at least a son from the earlier marriage of John I and Alice Young. He was alive in 1471 but dead before 1483.

So perhaps all three sons were much older than suggested and the birth of Christopher in 1467 may simply mean that John III, the father of Christopher, had a family later in life?

But that also suggests that Alice, the mother of the three boys, would have been born about 1400 – or even earlier – and about 90 when she died, or that she married John I and did not have any children of her own.

One option is that Humphrey had, indeed, been born earlier to Alice I, but his two brothers were born to the second wife of John I – or these two were the sons of John II, making John II the brother of Humphrey, but this does not fit with the account in the levy.

Another possibility is that there were two Humphrey Codringtons, one a brother of John I and another his son. This would account for the earlier chancery records and for the younger Humphrey being escheator in 1467 some thirty years later.

Humphrey was alive until at least 14 May 1475 as shown by a record in the National Archives.

Debtor: Humphrey Codrington of Codrington in Glos., esquire, John Lypiat of Lasborugh in Glos., gentleman, and Thomas Payne, formerly of Gloucester, gentleman.

Humphrey may also have had a wife, Agnes, but I am not sure where this reference to Agnes comes from.

The name Humphrey may have come from the Poyntz family where it is not uncommon and this gives some weight to the idea that John’s mother was a member of the Poyntz family, and Humphrey was named after one of his grandmother’s relations.

The name Humphrey may have come from the Poyntz family where it is not uncommon and this gives some weight to the idea that John’s mother was a member of the Poyntz family, and Humphrey was named after one of his grandmother’s relations.

Like Humphrey, Robert Poyntz, of Iron Acton, was escheator of Gloucestershire 1395-7, 1399-1400, 1402-1404 (as well as sheriff 1396-97) so perhaps there is some earlier connection between the families than previously recorded.

Gotherington

Another record, however, suggests that Humphrey may not be what he seems.

There is another village in Gloucestershire called Gotherington, near Tewkesbury, and there is a record dated 1477 of another Humphrey there:

There is another village in Gloucestershire called Gotherington, near Tewkesbury, and there is a record dated 1477 of another Humphrey there:

Debtor: Humphrey Godryngton of Gotherington {Godryngton} in [Cleeve Hundred] Glos., esquire. Creditor: John Brugge, esquire. Amount: £80 of legal English money [£44,000].

In 1371 the manor of Gotherington appears to have been pretty run down and there seems to have been no connection to the Codryngton or even the Gotherington families.

No repairs have been done to the abbey church for three years past and more. The manor of Gotherynton lies waste.

It seems clear that one John Codryngton lived at nearby Clyfe [Bishop’s Cleeve] in 1421 and of Tewkesbury in 1423, but did he take his name from nearby Gotherington or was he part of the Codryngton family?

Gotherington itself seems to be a small village and if there was a family that took it’s name from the location there should be some record of them, and I can find none.

The village of Codrington is in the hundred of Grumbold’s Ash, some distance south of Tewkesbury, so there may have been some confusion between these two Humphreys, or at least how they have been identified in some records.

Possibly whoever wrote the document was mistaken and was familiar with the village of Gotherington but not with Codrington, and assumed the rest.

Or perhaps it was the creditor, John Brugge, that was from Gotherington and it was assumed that Humphrey was also from there having a similar sounding name.

The village of Codrington is also named Godrington in some references, and Gotherington, near Tewkesbury, was originally named Godrinton in the Domesday book, just to confuse things.

RHC identifies a long list of different spellings, all associated with the Codrington family, including Gooderington (but not Gotherington) but does this necessarily mean that all of these spellings should be taken as belonging to the same family?

RHC identifies a long list of different spellings, all associated with the Codrington family, including Gooderington (but not Gotherington) but does this necessarily mean that all of these spellings should be taken as belonging to the same family?

Codrington, itself, is not in the doomsday book, so could the family have originally come from Gotherington near Tewkesbury? The Gotheringtons then acquired land near Wapley that took it’s name from the family?

This would account for links to Clyfe and Tewkesbury in some documents, but if the family owned any land in that area there is no reference to it in the levy of fines or the inquisition after Alice’s death.

This could indicate that the Codringtons recorded as being of Clyfe and Tewkesbury were not from the same branch of the Codrington family, or maybe not even not Codringtons at all but Gotheringtons, who’s name had been changed?

There is also a manor on Devon named Godryngton [usually Godryngton and Norton].

There is records in the National Archives that casts doubt over the dates in the earlier chancery records relating to Humphrey Codrington, as mentioned above.

There is records in the National Archives that casts doubt over the dates in the earlier chancery records relating to Humphrey Codrington, as mentioned above.

The later dates shown below would fit much better with a later Humphrey in this case, presumably related to his position as Escheator for Gloucestershire:

Short title: Fouler v Codryngton.

Plaintiffs: Richard Fouler and John Sydenham, the younger.

Defendants: Humphrey Codryngton.

Subject: Wardship and marriage of Isabel de la Ryver, heiress of Maurice de la Ryver, esq., granted by the King to petitioners. Gloucestershire

Date: 1432-1443, possibly 1467-1470

If the earlier dates are incorrect then it makes it much easier to fit Humphrey as the eldest of three brothers born about 1425-1435 and for him to have been a respectable age as escheator of Gloucestershire.

Or perhaps there were two Humphreys – one the brother of John I and another his eldest son – who both held the position of escheator at different times?

RHC states that Alice Codrington, the widow of John Codrington, lived till 20th April 1489, six years after her sister Margery, widow of Peter Bessilles.

However the inquisition into her death taken on 20th September, 6 Henry VII [1490] says she died 16th July last so clearly something is not quite right – perhaps that was the date that the will was proved?

Because of the way that regnal dates are calculated – based on when the monarch acceded to the throne – 16th July 1490 would be 5 Henry VII although the precise date of her death is not specifically important at this point.

Other possibilities

If John II was from the first marriage of John I then this explains why the first son from his second marriage was named Humphrey and not John, but doesn’t help explain where the name came from, unless there was another, older Humphrey – possibly a brother to John.

The name does appear again in the Codrington family – although several hundred years later – and may have come from the maternal line of a previous marriage.

If the elder son John II died about 1445 then John I and Alice II could have named their second son John. The timing would be tight, but the birth of John III could be as late as 1445 based on the birth of his son Christopher.

Perhaps all the sons were from the first marriage and John I simply remarried after his first wife died, but had no further children?

This would certainly explain why the two eldest sons had died before their step-mother, but is in no way conclusive. It could also explain why the heir of Alice, Christopher, is described as cousin and not grandson.

But, if this were the case, Christopher, the son of John III, would have been born significantly earlier. We know that he was born about 1467 because in the inquisition following Alice’s death in 1489 he was 22 years old.

John I was shown to be married in 1429 [in the request for an altar], so there is time for his first wife to have died and for him to remarry and to have been the father of the three boys if they were born about 1435.

If John had already remarried by 1429 then the boys could have been born earlier – possibly 10 years earlier – than proposed.

Working backwards from Christopher it is possible to have a guess at the marriage of his parents and the birth of his father – assuming John II existed.

John I 1364 = Alice I, married about 1390

.. John II 1395 = Alice II, married about 1425

…. John III 1437 = Alice? Poyntz [i], married about 1465

…… Christopher 1467 = Ankarette Twynyho

If there was no first wife then I cannot see why John I would have waited so long after Agincourt to get married. After all he would have been about 60 years old – even his son John II, from his first marriage [if he existed] would have been 40.

It is curious that the term “and his wife then being” is used in granting the permission for the altar in 1429, but perhaps I am reading too much into this.

[i] The wife of Sir John Poyntz was Alice Cox, and there are no other daughters in the family pedigree with this name so it is possible, even likely, that there would have been a daughter named Alice after her mother.

CXI Investigations

Perhaps the age on the tomb is wrong, as suggested earlier, and John actually died at 91 – still a remarkable age – so he then would have married at the age of about 35, after Agincourt.

This does mean that there was probably another John, his father, as suggested, but it was the younger John who was at Agincourt and not the elder and this fits with an older John marrying well before Agincourt and John II marrying Alice Hawys.

There is also another name mentioned as the first wife of John I, Margery Chalkley, and two sons John and Geoffrey, so perhaps there was only one wife named Alice? Or the second Alice was married to his son John?

This could fit well with John I being born earlier – perhaps about 1360 with father Robert being about 35 years old – and John II being born about 1385, along with sister Margaret who could have been named after her mother.

It also makes his later marriage much less unusual as it fits exactly with the average marrying age of Codrington men of 35. The earlier John could even be the one who was attorney to the king in 1337, as mentioned below, but I think this would be too early and John the attorney is more likely from a different branch of the family or an earlier generation.

Robert also seems to have lived a long life if he died after 1419, and it is therefore also likely that he was the younger brother of John I as he did not inherit the Codrington property and is only ever recorded as being of Chipping Sodbury.

I would guess that John I probably died before Agincourt, or was certainly too old to take part and this leaves the earlier Codrington tree looking a bit different …

Geoffrey 1300-

.. Robert I 1330-

…. Robert II 1360- 1419 of Chipping Sodbury

…. John I 1360-

…… John II 1384 – 1475 of Agincourt

If John was born in 1384 then Margaret, who married John la Veale could not have been his daughter or sister, but can only have been an aunt, if she married and had a son and daughter [and died] by 1409.

The other Geoffrey

An earlier John, apprentice and attorney to the king in 1337 [see below], could have been the brother of the earlier Robert and have been the grand-father of John of Clyfe and Tewkesbury

He could even have been the one who was married to Margery Chalkley and the father of John and Geoffrey.

Geoffrey Codrington appears in a document about the Percy family of Great Chalfield, Wiltshire, where he is shown to have married the grand-daughter of Constance – cousin to the bishop of Salisbury – who married into the Percy family.

I have estimated that Geoffrey was born about 1370 based on his marriage to Isabel Beaushyn [and her estimated birth] and he was the father of Alice Codrington, born about 1400, who married Alexander Martin.

I have estimated that Geoffrey was born about 1370 based on his marriage to Isabel Beaushyn [and her estimated birth] and he was the father of Alice Codrington, born about 1400, who married Alexander Martin.

Isabel Beaushyn born about 1380, was the daughter of Thomas Beaushyn of Dorset and Joan Fitzwaryn, who was the daughter of Constance [who married a Percy] by her third husband, Sir Philip Fitzwaryn.

The same document about the Percy family also makes reference to Thomas Ivye of Sherston who married Agnes Tropenell and may have a connection to Susan le Veele mentioned earlier.

If the first marriage of John Codrington was to Margaret Chalkley and they had sons John and Geoffrey, then could these fit into the main Codrington tree?

Geoffrey probably married Isabel Beaushyn about 1400, putting his birth about 1370. If he was a younger brother to John of Agincourt, born in 1384 then this would be practically impossible.

Sir Philip Fitzwaryn and Constance, Isabel’s grand-parents, married about 1361 – Philip was the third wife of Constance. This means that their daughter Johan, could not have been of an age to marry much before 1380. Her daughter, Isabel, could have been born about this time and married before 1400 but not by much.

Perhaps Geoffrey was the elder brother of John but died shortly after his marriage to Isabel leaving one child – daughter Alice – and his brother John as the heir?

Isabel later remarried to William Haukesoke.

[More information shows that Geoffrey and Isabel were a generation later]

It is possible that Geoffrey married Isabel towards the end of the 14th century but then died before he inherited from his father. But he would have been quite a bit older than brother John for this to be possible.

John I (1335) = Margery Chalkeley

.. Margery (1365) = John le Veale

.. Geoffrey (1370) = Isabel Beaushyn

.. John II (1384) of Agincourt = Alice Hawys

It also squeezes Robert out as the father of John I as the marriage of John and Margery would have been much too early considering he was alive in 1419, but he could still be another brother of the elder John.

There is even time here for a third John Codrington [and another Alice] if John II was born about 1365, in which case Margery would have been his aunt and not his daughter.

John I (1335) = Margery Chalkeley

.. Margery (1365) = John le Veale

.. John II (1365) = Alice Young

…. John III (1384) of Agincourt = Alice Hawys

.. Geoffrey (1365) = Isabel Beaushyn

Robert Codrington of Chipping Sodbury could fit into this tree as the brother of John II and Geoffrey, but probably not the father of John III of Agincourt.

There is a link to the Chalkley family through Margery Hawys – the sister of John Codrington’s wife, Alice – and her second husband William Warbleton.

In 1460 he and his wife recovered £120 [£62000] damages from Thomas Chalkley of Clanfield, Oxfordshire.

I have not been able to find any more information about the Chalkely family.

William Warbleton was also at Agincourt in the retinue of the King himself.

Thomas Codrington

So what, then, of Thomas, supposedly the brother of John Codrington of Agincourt and the head of the junior branch of the family?

So what, then, of Thomas, supposedly the brother of John Codrington of Agincourt and the head of the junior branch of the family?

His position in the tree is identified by the arms that were used by the family and were those originally used – and then modified – by John of Agincourt before 1441.

Both of these arms can be seen in the stained glass window of the Castle house in Calne, Wiltshire as described by RHC in his first work on the Codrington family.

The modified version of the arms was then used by the senior branch of the family and the original arms by the junior, as shown in The Codrington Arms.

The declaration in 1419 by Henry V seems to have been the point when the use of arms was formalised as being only by inheritance or by a grant from the crown, and before this date the use of arms may not have been so rigorously controlled.

It seems that Thomas, who heads the junior branch of the family, is unlikely to be Thomas, the son of John and Alice, as he would have used the arms of his father.

It seems that Thomas, who heads the junior branch of the family, is unlikely to be Thomas, the son of John and Alice, as he would have used the arms of his father.

Seemingly to contradict this the arms I have used in this article, as those of John Codrington of Agincourt, are actually titled – in their original document – as the arms of Thomas Codrington in the 15th century.

The only Thomas around in the 15th century was Thomas the son of John who was known to be alive in 1489 when his mother died.

RHC identifies Thomas as B1, the head of the junior branch, and then assigns son Ambrose as B2 followed by William B3 and makes William the husband of Mary Teste, but this is based on Thomas having died in 1427 [6 Henry VI] and being the brother of John of Agincourt.

B1 Thomas (d.1427, 6 Henry VI)

.. B2 Ambrose (b.1425) [#1]

…. B3 William (Married to Mary Teste)

…… B4 Francis (b.1512) = Margaret Shipman

[#1] Because of the date for the death of his father, Ambrose must have been born before 1427.

Most pedigrees acknowledge Ambrose as being the husband of Mary Teste and if Thomas was born about 1435 [and the son of John] then Ambrose could have been married to Mary and William probably did not exist – or at least was a brother.

William B3 does not appear in the Codrington pedigree held by the College of Arms, and neither is he in the pedigree shown in “memoirs” despite being added to the line of inheritance later in the document.

If there was a simple transcription error for the death of Thomas, and it should be Henry VII instead of Henry VI, then his death would have been 1490, which fits with him being alive at the inquisition of Alice in 1489 and the birth of Ambrose would be around the same time as his cousin, Christopher, which we know was 1467.

The manor of Frampton on Severn was bequeathed by Giles Teste [who inherited from his father Lawrence] to his sister Mary, the wife of Ambrose Codrington, on his death in 1545.

If Ambrose was alive at this time – Mary is not shown as a widow – he would have been about 80 years old – but would certainly not have been alive if his father, Thomas had died in 1427.

Assuming Thomas is the son of John A1 and brother of John A2 things do fit much better and we can leave out William altogether.

B1 Thomas (d.1490, 6 Henry VII )

.. B2 Ambrose (b. about 1465) = Mary Teste

…. B4 Francis (b.1512) = Margaret Shipman

Some lands were granted specifically to Thomas, the son of John and Alice, in the 1471 Levy of Fines, so it would be interesting to see who actually inherited these properties.

And besides after the decease of John Codryngton’ and Alice 6 messuages, 2 tofts, 1 garden, 1 dove-cot, 100 acres of land, 30 acres of meadow and 40 acres of pasture in the vills of Bristoll’, Leyghterton’, Haukesbury and Upton’ Hamell’ shall remain to the aforesaid Thomas, son of John Codrynton’ and Alice, and the heirs of his body, to hold of the chief lords for ever.

Thomas was known to have be at Chipping Sodbury in 1474 – from documents relating to Alderton Manor – possibly in the property previously occupied by Robert.

The Overseers were Sir Richard Beuchamp of Bromham, Sir John Seyntlow of Tormarton and Thomas Codryngton of Chepynge Sodbury, signed at Lockyngton 1st March. These are the names on the indenture renting Alderton to the Pophams.

The only reference we have to his father, Ambrose, shows that he was living in Bristol 1501 where he was a trustee of the Fraternity of the Blessed Mary of Bellhouse, a chapel in the church of St Peter’s, but it is likely that he lived until at least 1545.

Junior Branch

So was the junior branch actually descended from Thomas the son of John Codrington of Wapley and not his brother?

If so then why are all the arms of the junior branch in the window of Castle House at Calne shown as a different version of the arms and not those used by his father?

In the section of “memoirs” on the junior branch, RHC says that Thomas – as the head of the junior branch – was shown as the son of John of Codrington in a pedigree held by the Heralds College [possibly the one shown below], and married to Elizabeth the daughter of Robert Poyntz, but that some other pedigrees disagree.

As Robert Poyntz was a generation before Nicholas [mentioned above] it seems that a daughter Elizabeth would have been much to old to have married this Thomas, but could have married a brother of John of Agincourt.

The main reason for assuming that the head of the junior branch was a brother of John Codrington of Wapley are the use of the original arms – and not those of John himself, but the pedigree of the Poyntz family also seem to play a role in this.

If Thomas was the son of John of Agincourt then both he, and his brother John, appear to have married into the same generation of the Poyntz family.

I can find lots of issues with both of these scenarios. But perhaps there is another answer to this – perhaps the head of the junior branch is neither the brother of John, or his son?

One pedigree say that Thomas died in 1427 and RHC says that he belongs to an earlier generation than John Codrington A2 as does Ambrose, the son of Thomas, but this is based on his brother, John, having been born 1364.

If we assume that John was actually born 20 years later then originally thought – dying at the age of 91 – then Thomas could actually be an uncle to John and brother of Robert, his father. He could also have been the brother of John, born about 1385, and dying at the disappointing age of just 42.

But that still leaves the mysterious William having to fill in the missing generation in the early pedigree of the junior branch.

The 1623 visitation of Gloucestershire does show William Codrington as being married to Margaret Teste, the daughter of Lawrence.

Interestingly the arms of this William are shown as those of John Codrington A1 with the embattled fesse and not those used by other members of the junior branch.

There is also another Margaret shown in the tree and a reference to Mary, but the son of William is shown as Gyles missing out Francis [born in 1512] so this information may not be entirely accurate – especially as it is shown as part of the Clifford pedigree and not specifically the Codringtons.

Will.i.Ambrose

The name used in the pedigree should be Ambrose and not William. But where did the name William come from?

I think that this was just a simple mistake:

The pedigree was taken from the visitation of Gloucestershire in 1623, but the Codrington family are included only as part of the Clifford family. It is likely, therefore, that the person giving evidence to the visitation was not actually a member of the Codrington family.

Francis Codrington, born about 1512 who married Margaret Shipman, is missing from this pedigree, so clearly there is a gap in the knowledge of the Codrington pedigree.

I think the name William came from the father-in-law of Francis, William Shipman.

If Ambrose had died relatively young – few records exist of him – then his name may not have been well-known to the Clifford family and William was a prominent merchant as well as being major of Bristol in 1533.

Francis and William were both in shipping, no doubt Francis was taken into the family business after his marriage to Margaret. Francis was made burgess of Bristol in 1532.

The missing generation is possibly why the names of both Mary and Margaret are shown as the wife of “William” in the pedigree.

Records show that Ambrose of Bristol, son and heir, married Mary (Maria) Teste and Francis married Margaret Shipman. The will of John Shipman confirms that Francis married Margaret and not Mary, making it more likely that Ambrose (William) married Mary.

So it appear to me that two generations of the Codrington family have simply been mis-remembered and mixed up in the Clifford tree.

Wives and Daughters

RHC says that the wife of John Codrington A2 was a daughter of Nicholas Poyntz of Iron Acton, based on the work done by Sir John Maclean.

However this is incorrect as the pedigree actually shows that this was the daughter of John Poyntz [son of Nicholas] and Alice Cox, and RHC may have been simply mistaken.

John Poyntz was born about 1433 and had died by 1468, so a daughter is likely to have been born around 1450 and this could fit with a daughter – possibly named Alice after her mother – marrying John Codrington A2 with a son Christopher being born 1467.

Thomas Codrington is also shown to have married Elizabeth Poyntz and if he was the brother of John then Elizabeth must have been a sister, or cousin of whoever John married.

As can be seen from the pedigree above [from Sir John Maclean’s “Memoirs of the Poyntz family”], Elizabeth, the sister of Alice and daughter of John Poyntz, does not seem to have been married at all so it is not clear who this Elizabeth was.

The pedigree from the College of Arms says that she was the daughter of Sir R Poyntz.

Sir Robert Poyntz, of Iron Acton, was the brother to the daughter of John Poyntz said to have married John Codrington A2, and apart from the obvious date problems his daughter, Elizabeth, is shown to have married Nicholas Wykes of Doddington.

Sir Robert Poyntz, of Iron Acton, was the brother to the daughter of John Poyntz said to have married John Codrington A2, and apart from the obvious date problems his daughter, Elizabeth, is shown to have married Nicholas Wykes of Doddington.

An earlier Robert Poyntz Esq. was born 1359 and was the father of Nicholas, and grandfather of Sir Robert but this would be much too early and there is no record of a daughter Elizabeth.

Perhaps John the younger actually married someone else – possibly Alice Young, as shown in the College of Arms pedigree – and it was his brother Thomas that married a daughter of John Poyntz and not Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Robert?

Alice could then have been the daughter of Thomas Young [who was born about 1420] as mentioned in the college of arms pedigree.

A1 John Codrington = Alice Hawes dau. John

.. A2 John Codrington = Alice Young dau. Thomas [born about 1450]

.. B1 Thomas Codrington = Elizabeth Poyntz dau. John

Perhaps both John and Thomas married daughters of John Poyntz, but only John seems to have been remembered [even if the name of his wife is not].

The visitation of Gloucestershire in 1623 shows Elizabeth as the daughter of John Poyntz and Alice Cox and married to an unknown son of an unknown Codrington.

This daughter is also shown as the wife of Robert Veale and it appears that Thomas could have married the widow of this Robert and John, perhaps, married the other unidentified daughter “Alice”.

In “memoirs of the Poyntz family” Elizabeth is shown only as being nurse to a son of Henry VIII in 1510, but she could have been the widow of both Robert Veale and Thomas if he had died in 1490.

Perhaps Sir John Maclean simply did not appreciate that Elizabeth and the unknown daughter who married a Codrington were one and the same?

The pedigree held by the College of Arms is quite interesting in that it shows Humphrey, John and Thomas as the three sons of Robert Codrington.

Based on other documents – such as the levy of fines and the inquisition into the death of Alice – this cannot be correct and the pedigree is missing several generations, but somewhere hidden in here – no doubt – is some truth.

Other Codringtons

John Codrington of Codrington and Wapley is not the earliest person recorded with that name and in 1337 one John Codrington was “apprentice to our lord the King [Edward III], and attorney”.

It seems he is recorded in history because he had been commanded to attend Sir John de Ros, at Orwell on 17th March 1337 and wasn’t too happy about it:

“…well and completely armed and apparelled as a man-at-arms, and that, upon pain of being hanged.”

John petitioned the king to be excused this service and seems to have earned a reprieve.

“Inasmuch as he is an attorney, let it be commanded to Sir J. de Ros, or his lieutenant, that they surcease from the demand which they make about him, and the distress which they do to him for this cause.”

The hundred year war with France started in this year so no doubt the command was related to the formation of armies for the campaign.

Whether this John lived in Gloucestershire is not recorded, but there are no other branches of the family known at the time in other parts of the country.

One Sir John Coderyngton appears in records relating to the seizing of the Chantries in 1547 during the first year of the reign of Edward VI.

He was the incumbent of Holy Trinity, Dursley, Gloucestershire and was paid to say prayers for the deceased, his income coming from endowments left for the saying of masses.

… of the age of 80 years, and having no other living than in the said service, which amounted to £6 13s. 4d.

This may be the same John Coderyngton who, 20 years earlier, was the prior of the rather unruly Malmesbury Abbey.

… Thomas Gloucester had often cast away his habit, had climbed over the walls and consorted with harlots, and had seized the possessions of others for his own use, and John London was nearly as bad, and had apostatized and offered violence, and Robert Ciscetur was frequently drunk. Other monks, continued the abbot, were little better: several had broken out at night, the prior, John Codryngton, was remiss and openly admitted it in light-hearted fashion …

The title Sir John Codryngton must have been an affectation as there are no records for a Sir John. He would have been born about 1467 but there is no obvious place in the senior Codrington tree for him.

Probably then he is from the junior branch of the family, a younger brother to William [Ambrose] Codrington, born 1462 of Frampton-on-Severn? It was often the younger sons that went into the church and his age fits with this scenario.

Stephen Codrington is mentioned in Notita Monastica  in relation to Stanlegh Abbey in Wiltshire, 1379. He could easily be a cousin or even brother of John Codrington I and I think this must be the first reference to any of the Codrington family being of Codrington and Wapley.

in relation to Stanlegh Abbey in Wiltshire, 1379. He could easily be a cousin or even brother of John Codrington I and I think this must be the first reference to any of the Codrington family being of Codrington and Wapley.

2 Ric. 2. receit. et confirm. donationes: P. 869. cart. antiq. X. n. 6, fcil. 2 Ric 2. confirm. donationem R. fil. Stephani de Codinton et Wapalee.

This appears to be a record of a donation to the abbey and there are also references in the same book to the manor of Codrington with a much earlier date.

15 Ed 1 [1286]. quo war. rot. 7. d. pro libertat in maner de Codrington [for freedom in the manor of Codrington].

It was John Codrington [of Agincourt] who purchased the manor at Codrington from Stanlegh Abbey about 60 years after the record of the donation by Stephen, and this does show family connections with the Abbey. The abbey also had connections to St. Augustine’s in Bristol where Robert Codrington was later buried – St Augustine’s was also the parent church to St Peter’s in Wapley.

Pat. 33 Hen 6 [1454] p. 2. m.. de maner. de Codrington [Gloucestr.] concedendo Joanni Codrington: fin. div. com.

Could Stephen actually be the father of John Codrington I with John Codrington II being his son and the one who was at Agincourt?

What we can surmise from this record is the possible age of Stephen. In order to be in a position to make a donation to the abbey he must have been successful and probably not a young man. We could also say that he was of an age to “contemplate his own mortality” and was probably making a donation to the abbey in preparation for his after-life, possibly for prayers to be said for him, as done by John Codrington and Alice [see below].

Based on this I would estimate his age as about 50 years old and therefore born in 1329. This is not an exact science but does give us some idea of which generation he belongs to.

If John was born in 1384, and died aged 91, then it is unlikely that Stephen was his father and more likely an uncle. If this was the case then John, or more likely his father, was Stephen’s heir – somehow or other John inherited the property at Codrington and Wapley.

I am only exploring possibilities and my own ideas here – there are are lot of facts that just do not quite fit. A later birth date for John and shorter life of 91 would go some way to make this puzzle a little easier to understand, but there is no evidence that the age on the tomb is incorrect.

I am only exploring possibilities and my own ideas here – there are are lot of facts that just do not quite fit. A later birth date for John and shorter life of 91 would go some way to make this puzzle a little easier to understand, but there is no evidence that the age on the tomb is incorrect.

Whatever actually happened, and who is related to who, may never be known for sure – perhaps a combination of several of the above scenarios? There is time in the life of John for him to have married at least three times (or more) and to have had several families – even if he only lived until the age of 91.

Or maybe I am too doubting and it was simply as RHC surmised:

John returned from Agincourt, married a young woman, survived his son, and died in extreme old age.

Although I am not sure that he fully believed that this was correct.

I will be updating my family tree to take into account some of the ideas that I have discussed, to better fit with other pedigrees, and adding John II, based on very little evidence.

I will be updating my family tree to take into account some of the ideas that I have discussed, to better fit with other pedigrees, and adding John II, based on very little evidence.

If the age on the tomb is correct then my best guess is that John Codrington had two wives, with his children all being born from his first marriage, which is why two had died before his second wife. After the death of Alice I he remarried but did not have any more children.

What confuses this slightly is the birth of grandson and heir Christopher, who’s father would have been quite old when he was born in 1467, but you can’t have everything.

If the age on the tomb is incorrect and he died aged ninety-one, then things become a little easier to understand with John at Agincourt aged 30 and married shortly afterwards.

Personally this scenario appeals to me as it is much neater and fits with most other facts and estimates, and I will be pursuing this further.

In this case Robert could be the younger brother of John I and therefore the uncle of John of Agincourt, which is why he was only ever of Chipping Sodbury and did not inherit Codrington and Wapley.

Both John I and Robert could also be the sons of Stephen who is shown to be of Codrington and Wapley in 1379 or possibly John Codrington who married Margery Chalkeley.

Stephen of Codrington and Wapley

.. John I

…. John II of Agincourt = Alice Hawys

…… Humphrey – Escheator of Gloucestershire

…… John III

…….. Christopher – Heir of Alice

…… Thomas

…. Robert of Chipping Sodbury

…. Thomas [junior branch]

I think there is also enough evidence to say that it is more than likely that Thomas B1 was the son, and not brother, of John A1.

This does mean, technically, that John III should be the head of the senior branch A1 and not John of Agincourt.

The Elder Tree

Some additional information about Geoffrey Codrington and Isabel Beaushyn has made me change a few things – in particular they are shown elsewhere to be a generation later than I have estimated – meaning that Geoffrey is probably the brother of both John of Agincourt.

This makes John and Margaret Chalkley the parents of John of Agincourt leaving Alice Young to be the wife of John’s son John [father of Christopher].

Margaret – who married John le Veale – must also be the sister to John II and Geoffrey II.

But this does mean that there is a generation missing between the earlier Geoffrey I [estimated as being born about 1300 by RHC] and John I. Possibly the earlier Geoffrey was a generation later and Geoffrey II was his son [and named after him]. He could also have been the eldest of the two brothers, but died without a son leaving John II as the heir.

As Peter of Codrington and Wapley was recorded making a donation to the Abbey of Stanleigh in 1379 he must have been about 50 and therefore could fit into the gap between Geoffrey I and John I. Robert of Chipping Sodbury then becomes the brother of John I and the uncle of John II of Agincourt. John I would have inherited the Codrington property from his father, Peter, and passed it to his son.

There is a reference to Richard Goderyngton, who was shown as Deacon in the records of Bishop William Ginsborough for 1304/5, and this is now the oldest record I have found, assuming Richard is a member of the same family.

Another John Codrington – attorney to the king in 1337 – is probably related to this Richard or his son Geoffrey. Other records show that there was a branch of the family based around Tewksbury and Gloucester. This, perhaps, shows a link between the Codrington family of Wapley and the village of Goderyngton although it is also possible that the two are not related.

Richard Goderyngton (1275)

.. Geoffrey (1300)

.. Ralph

.. Thomas

.. John (1325) Attorney to the King

…. John (1350)

…… John (1380) of Bishop’s Cleeve

…….. Anselm Codrington of Gloucester

From all the information available at the moment the early Codrington pedigree could be something like this:

Richard (1275)

.. Geoffrey (1300)

…. Peter of Codrington & Wapley (1330)

…… Robert of Chipping Sodbury

…… John I (1360) = Margery Chalkley

…….. Margery (1390) = John le Veale

…….. Geoffrey (1385) = Isabel Beaushyn

…….. John II A1 (1384) of Agincourt = Alice Hawys

………. Humphrey = ?Agnes?

………. John III A2 (1435) = Alice Young

………… Christopher A3(1467) = Ankarette Twynyho dau. William *

………….. John A4 (1490) = Dorothy Fettiplace

………… Edward A7(1469) = Elizabeth Tywnyho dau. John

………….. Thomas A8 (1515) = Mary Kellaway

……………. Simon A9 (1554) = Agnes Seacole

……………… Robert A11 (1574) = Anne Stubbes dau. Willliam

………. Thomas B1 (1435) = Elizabeth Poyntz

………… Ambrose B2 (1470) = Mary Teste

………….. Francis B4 (1515) = Margaret Shipman dau. William

……………. Gyles B5 (1535) = Isabella Porter

……………… Francis B6 (1559) = Margaret Bromwich *

……………… Richard B7 (1560) = Joyce Burlace

* Line passed to brother/heir.

The wife of John Codrington was Alice Hawys. This has also been transcribed as Hannys and Hauuys which is understandable. Alice’s sister Margery is also named as Hawes and Haines, in documents relating to the will of Peter Bessiles. I have stuck to the Hawys spelling for consistency as much as possible.

The wife of John Codrington was Alice Hawys. This has also been transcribed as Hannys and Hauuys which is understandable. Alice’s sister Margery is also named as Hawes and Haines, in documents relating to the will of Peter Bessiles. I have stuck to the Hawys spelling for consistency as much as possible.

Another record, not mentioned by RHC, is that John and Alice Codrington paid for a chantry in the Dominican friary at Bristol.

Another record, not mentioned by RHC, is that John and Alice Codrington paid for a chantry in the Dominican friary at Bristol.

John and Alice Codryngton of Gloucestershire established a perpetual chantry in 1469 in the Dominican house at Bristol where a daily Mass was to be celebrated for the benefit of their souls, those of their ancestors and all the faithful departed, with additional services for their anniversaries.

John Codrington I would have been over 100 years old at this time and even a younger John would have been 80.

Chris Sidney 2015

I have recently obtained a copy of Ruth Hughey’s book John Harington of Stepney: Tudor Gentleman, published in 1971. How does it compare to my own research and does it contain any other useful information?

I have recently obtained a copy of Ruth Hughey’s book John Harington of Stepney: Tudor Gentleman, published in 1971. How does it compare to my own research and does it contain any other useful information? Ruth includes a portrait of John, clearly in his later years. This is held by the Victoria Gallery in Bath and although it has not been authenticated as being John Harington of Stepney it came originally from the Harington family portrait collection.

Ruth includes a portrait of John, clearly in his later years. This is held by the Victoria Gallery in Bath and although it has not been authenticated as being John Harington of Stepney it came originally from the Harington family portrait collection. In some commentaries John is said to have been organist at the chapel royal in 1540 [which would again imply that he was older than 13] but this is incorrect and it was Thomas Tallis who became organist at this time and John studied music under him.

In some commentaries John is said to have been organist at the chapel royal in 1540 [which would again imply that he was older than 13] but this is incorrect and it was Thomas Tallis who became organist at this time and John studied music under him.

Ruth noted that it was not until 1597 that Sir John Harington was finally granted the right to use the arms of the Brierley branch of the family – the single fret design.

Ruth noted that it was not until 1597 that Sir John Harington was finally granted the right to use the arms of the Brierley branch of the family – the single fret design. One thing that is cleared up in the book is the names of the two Gloucestershire manors – Bibury and Alrington – that John purchased in 1547 in exchange for his annuity from the lordship of Denbigh that he had been granted nine years earlier.

One thing that is cleared up in the book is the names of the two Gloucestershire manors – Bibury and Alrington – that John purchased in 1547 in exchange for his annuity from the lordship of Denbigh that he had been granted nine years earlier.

Recent Comments